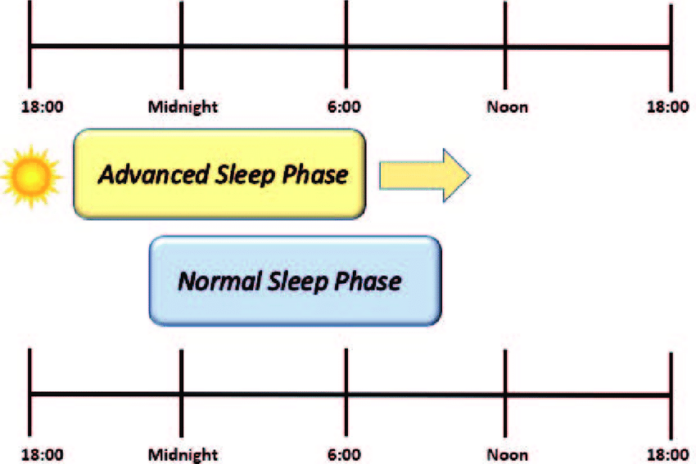

Advanced sleep phase disorder, often called advanced sleep-phase type (ASPT) of circadian rhythm sleep disorder, is a syndrome marked by a repeated pattern of very early morning awakening (e.g., 2-4 AM) and early evening (e.g., 7-9 PM) lethargy. This advancement of the sleep phase causes shorter sleep duration and excessive daytime tiredness, and it might disrupt daily social and work schedules.[1] The suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus is home to the body’s central circadian clock, which controls the time of sleep and melatonin levels.[2]

Signs and symptoms

People with ASPD report having early morning insomnia, falling asleep too soon and/or early in the evening, and being unable to stay awake until their preferred waking time. They also report being unable to stay awake until traditional bedtime. The core body temperature and melatonin levels of an individual with advanced sleep phase disorder cycle many hours ahead of average.[3] For a proper diagnosis, these symptoms have to be present and stable for a significant amount of time.

Why customised medicine can benefit from India’s first comprehensive healthy microbiome map

Diagnosis

A range of techniques and examinations can be used to diagnose ASPD in those exhibiting the aforementioned symptoms. Sleep specialists assess the patient’s melatonin onset in dim light, measure the onset and offset of sleep, and analyze the results of the Horne-Ostberg morningness-eveningness questionnaire. A polysomnography test may also be performed by sleep specialists to rule out other sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy. The patient’s age and family history are also taken into account.[2]

Caregiving

After a diagnosis, ASPD can be treated behaviorally with chronotherapy or with bright light therapy in the evenings to postpone and counterbalance the onset of sleep. Because it carries hazards to provide sleep-promoting medications early in the morning, pharmaceutical approaches to treatment are less effective.[1] Other therapy approaches, such as hypnotics or scheduled melatonin delivery, have been suggested; however, further research is needed to determine their safety and effectiveness.[4] Different from other sleep disorders, ASPD does not always interfere with daily functioning at work, and some patients may not report excessive daytime sleepiness. An someone may remain up later than their circadian rhythm dictates due to social obligations, but they will still get up quite early. This cycle has the potential to cause various sleep disorders as well as chronic sleep deprivation.

Statistical Analysis

Middle-aged and older persons are more likely to suffer from ASPD. Men and women are thought to be equally affected by ASPD, which is thought to afflict 1% of middle-aged individuals. A significant familial tendency is present in the disorder; 40–50% of those affected have relatives who also have ASPD.[5] Familial advanced sleep phase syndrome (FASPS), a variant of ASPD, has a genetic foundation. The advanced sleep phase phenotype is caused by missense mutations in the genes hPER2 and CKIdelta.[5] The discovery of two distinct genetic variants raises the possibility that this illness is heterogeneous.[1]

Familial advanced sleep phase syndrome

FASPS symptoms

The extreme phase advance characteristic of family advanced sleep phase syndrome, sometimes called familial advanced sleep phase disorder, is uncommon, despite the fact that advanced sleep and wake periods are very frequent, especially among older persons. People who have FASPS often sleep from 7:30 p.m. to 4:30 a.m., falling asleep and waking up four to six hours earlier than the general population. Additionally, their free running circadian period is 22 hours, which is far lower than the somewhat longer 24-hour norm for humans.[6] Because of the shorter time frame linked to FASPS, there is a reduction in activity, which causes an earlier onset and offset of sleep.This implies that in order to acclimate to the 24-hour day, people with FASPS need to postpone the commencement of their sleep and offset it every day. People with FASPS experience a further advance in their sleep phase on weekends and vacations, when the ordinary person’s sleep phase is delayed in comparison to their working sleep phase.[7]

In addition to their atypical sleep schedule, FASPS individuals get regular sleep in terms of both quantity and quality. Similar to general ASPD, this syndrome does not always have harmful effects. However, societal standards may force people to postpone sleep in order to meet social expectations, which might result in them waking up earlier than usual and losing sleep as a result.[7]FASPS is unique among advanced sleep phase disorders in that it exhibits a strong familial propensity and lifetime manifestation. FASPS is an autosomal dominant trait that affects about 50% of closely related family members, according to studies on affected lineages.[8]

By identifying the genetic variants known to cause the illness, genetic sequencing data can be used to confirm the diagnosis of FASPS. Although bright light therapy and sleep and wake scheduling can be used to try to delay the sleep phase to a more typical time frame, treatment for FASPS has generally failed.[9] Patients with FASPS or other advanced sleep phase disorders been proven to have later sleep onset and offset as a result of bright light exposure in the evening (between 7:00 and 9:00), during the delay zone as evidenced by the phase response curve to light.[1]

Exploration

When Louis Ptáček discovered people who had a genetic basis for an advanced sleep phase in a 1999 study at the University of Utah, he came up with the name familial advanced sleep phase disorder. “Disabling early evening sleepiness” and “early morning awakening” were noted by the first patient assessed for the study; her family members also reported having comparable symptoms. The first patient’s consenting relatives were assessed, along with those from two other families. A short endogenous (internally derived) period was linked to a hereditary circadian rhythm variant that was defined by the clinical histories, sleep logs, and actigraphy patterns of the subject families. The individuals’ sleep-wake cycles showed a phase advance that set them apart from both the control group and the generally accepted traditional sleep-wake patterns. The Horne-Östberg questionnaire, a standardized self-assessment tool used to measure morningness and eveningness in human circadian rhythms, was also employed to assess the respondents. The’marry-in’ spouses and unrelated control subjects had lower Horne-Östberg scores than the first-degree relatives of the ill patients. Even though morning and evening preferences are mostly inherited, it was proposed that the allele responsible for FASPS had a quantitatively greater impact on clock function than the more prevalent genetic variants that affect these preferences. Furthermore, plasma melatonin and body core temperature measurements were used to assess the individuals’ circadian phase; both rhythms were shown to be 3.4–5 hours ahead of phase in FASPS subjects as compared to control subjects. A pedigree of the three FASPS kindreds was also created by the Ptáček group, and it clearly showed autosomal dominant transmission of the sleep phase advance.[10]Phyllis C. Zee’s research group phenotypically described another ASPS-affected family in 2001. A Horne-Östberg questionnaire was used to analyze sleep/wake patterns, and a pedigree for the affected family was created as part of this study. According to the established ASPS criteria, the assessment of the subject’s sleep architecture showed that the advanced sleep phase was caused by a change in circadian timing instead of an exogenous disruption of sleep homeostasis, which is a mechanism of sleep regulation that is derived from the outside. Moreover, the family that was found had a person with ASPS in every generation; this pattern is similar with previous research conducted by the Ptáček group and indicates that the phenotype segregates as a single gene with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance.[11]

A genetic investigation of people during the advanced sleep phase was published in 2001 by the research groups of Ptáček and Ying-Hui Fu. The analysis revealed that a mutation in the CK1-binding region of PER2 was responsible for the behavioral trait known as FASPS.[12] The first condition to directly associate human circadian sleep disorders with known core clock genes is FASPS.[13] Since FASPS is not solely caused by the PER2 mutation, ongoing research has kept analyzing cases to find additional mutations that exacerbate the condition.