Aaditya Dhingra makes full use of FIDE’s rating system to become one of the world’s highest rated IMs. In comparison, India’s Gukesh D gained only 19.3 points in total ratings between June and August.

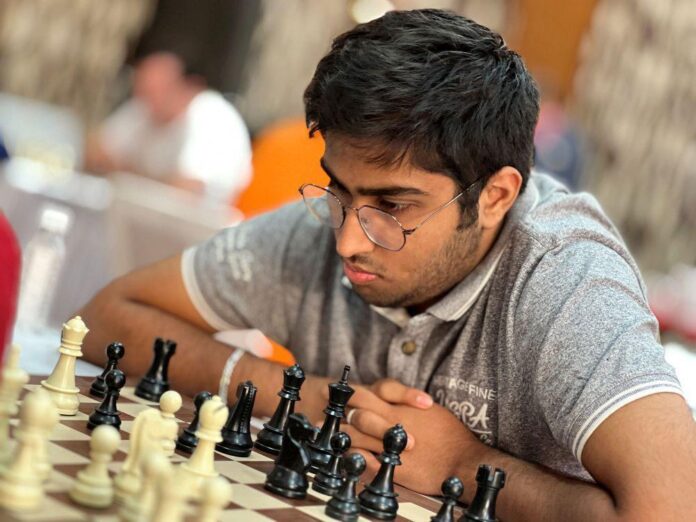

When Gurugram-based chess player Aaditya Dhingra’s rating skyrocketed from 2027 to over 2600 in three months, jaws fell and eyebrows arched in equal measure.

At the start of June 2023, Aaditya, who turns 17 on Sunday, has a rating of 2027 in FIDE’s public charts. But, thanks to a few tournaments in Serbia and the Maharashtra Open, his ratings have risen to 2144 in July and 2457 in August. He is anticipated to cross 2600 in the ratings that will be revealed on September 1, making him one of the highest rated IMs in the world.

With a rating of 2600, he has the potential to join the top 15 male Indian players. The average GM has a rating of 2500 to 2700, whereas players with ratings higher than 2700 are classified as Super GMs.

“When I planned my trip to Serbia, my goal was to simply become an international master, not to reach 2600 rating points.” That was the most important thing to me. I knew I had the stamina to be an IM. I had been chasing those IM norms for quite some time. I had only missed my norm in Nagpur in June (in the Maharashtra Open). “It was a great feeling when I got my first norm in Serbia,” Aaditya told The Indian Express, before adding, “If I’m crossing 2600, usme main kya kar sakta hoon?” (What should I do?) I’m aware of a problem with FIDE’s rules. But I can’t do anything about it.”

Despite the fact that no one in his family plays chess, Aaditya began playing in school in 2015 and has been a rated player since 2016. From February 2020 to January 2022, he was marooned at a rating of 2038

Aaditya’s meteoric climb is the result of clever calculations and a notion known as the development coefficient in the FIDE rating system formula. He participated in four tournaments, which contributed to his rise. In June, he won 117.20 rating points at the 2nd Maharashtra International Grandmaster Chess Tournament before flying to Serbia. He earned 188.10 points at the Novi Sad Vojvodin Open (June 28 to July 5), 124.64 points at the Paracin Open (July 7 to 15), and 151 points at Rudar 14 (July 26 to August 3).

He earned one IM norm at each of the three Serbian competitions. It is not uncommon for players to obtain three IM standards in a few of weeks. What drew attention to Aaditya’s performance was how he had amassed nearly 600 points in less than three months, while only participating in four events.

The reason lies in FIDE’s rather complicated method of calculating rating points and favoring youthful players.

In chess, there is a fundamental tenet: two players will not receive the same number of points for defeating the same opponent. The quantity of points a player receives for a win is determined by their chances of winning. Once these points are awarded for the win, they are multiplied by the player’s ‘k’ score. This ‘k’ score was developed to help younger players. Every child under the age of 18 has a score of roughly 40 (Aaditya had a k score of 40, then 38 as the months passed). When a player reaches the age of 18, but has not yet achieved the level of international master, the score drops to 20.

So, in essence, this k score influences how many points you score for a win. This is how Aaditya was able to dominate his four events. According to his Vojvodina Open statistics, he was able to add 34.96 points to his tally by defeating Shawnak Shivakumar in one game and 34.58 points by defeating Milos Pavlovic in another. Gukesh, India’s top-ranked player in the live ratings, with a total ratings rise of 19.3 points between June and August.

Aaditya was also employing some deft calculations. Playing in a tournament that began in July and ended in August meant that he was at his old rating of roughly 2100 in the first few games. When the August ratings were released, he had a rating of over 2450 (the k dropped to 10 as he crossed 2400). So, in those early games, he gained a rating as a 2100 player, so his scores were multiplied by 38 rather than 10. Aaditya was also slated to play in another tournament in Serbia, but he opted out of the classical event (he only played the blitz section).

“He should be commended for his astute tournament selection.” It’s extremely well done. All of this isn’t exactly new. People have been doing this for several years. This is the first time it has been done in this manner. Nobody has witnessed this type of growth,” said IM Rakesh Kulkarni, who also works for Chess.com India.

Chess.com, which broke the story first, investigated how long it took some of the game’s best stars to go from the 2000s to 2600. They saw that while Praggnanandhaa took just over four years to cover this rating distance, players like Gukesh, Magnus Carlsen, and Fabiano Caruana took over five years.

It should be stressed that there was no wrongdoing on Aaditya’s part in obtaining the points. However, his quick rise earned him considerable criticism on social media.

“I received a lot of nasty feedback. People from India and outside have been asking how this is feasible! No one has ever seen such a surge in rating points before. But I also received a lot of nice feedback, especially from friends and relatives. People who have seen me play used to tell me that I was underappreciated and that my strength was 2450 or 2500,” Aaditya, who practices with two of the country’s most known trainers, Visweswaran Kameswaran and GB Joshi, noted.

“Aaditya’s rise is remarkable, but not unprecedented.” Such increases are normally adjusted over time as the player continues to compete in tournaments,” FIDE’s Head of PR Anna Burtasova told this publication in an email.

She also offered a summary of ratings increases in a single month. According to the list, Islombek Sindarov of Uzbekistan gained 591 points in one month. Burtasova noted that Sindarov dropped 200 points after the high. She also noted that, in contrast to Aaditya’s situation, the greater issue confronting the chess world was “rating deflation” rather than inflation, as demonstrated in Aaditya’s case.

To address this issue, FIDE requested mathematician Jeff Sonas and his working group to analyze the system and make recommendations. The adjustments are currently being debated in public.

The few GMs contacted by this newspaper refused to comment. One of them suggested that rules include checks and balances to prevent a player from gaining too many rating points in a month.

Aaditya’s rating point surge was the result of a deft strategy and calculation, but there is little evidence to suggest anything unethical. Some on social media were quick to point out that a player racking up a lot of points at competitions in Serbia was suspicious. Many players have previously been able to rack up norms and scores of points at chess events held in Serbia. However, only one of the three Serbian events in which Aditya competed (Rudar 14) had his opponents known to him ahead of time due to the round-robin structure. The first two events were open tournaments, which meant that a player could only play nine of the 200 players in the pool. The player has no idea who they will play before the tournament begins, which negates the impression that players may agree on a specific outcome before the competition begins.